Wednesday

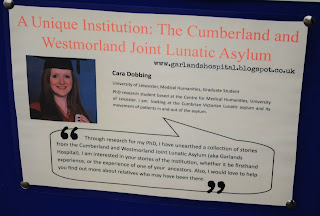

8th November saw the launch of our exciting project surrounding the

Garlands Asylum. Along with Cumbria County Council, Cumbria Partnership Trust,

and Carlisle Eden Mind, I presented some of my research, which focused on the

history of this fascinating institution. The aim of the project is to break

down the stigma surrounding mental health by opening up the discussion around

the treatment, as it was in the early days of the asylum, and as it stands now,

and the help people can access in the event of mental illness. The value of

reflection lies within the lessons we can learn from the progression in

terminology, treatment and the way we consider mental health. Through this post

I will outline the main points I made at the launch, and hope you will join the

discussion surrounding mental health.

My

focus, of course, is on the history of the Garlands Asylum, and how mental

conditions were treated in the period from its opening in 1862, until the

outbreak of war in 1914. Placing the patients’ stories and experiences at the

heart of my research has caused me to regard the institution with a human aspect.

When people ask about my research, and I mention the phrase ‘lunatic asylum’,

they have a large misconception about the brutality of treatment received, and

regard the institution with a degree of horror. Through my research I aim to

breakdown these misconceptions and retell its history through the patients who

experienced treatment in the institution.

My

talk began with giving a short background of the asylum: when it was

constructed, why, what kind of treatments were offered, and the effect this had

on the patients. I then set out the regime of care from the inception of the

asylum in 1862, and continued throughout the initial decades.

Moral Treatment

Moral

treatment, was advocated in all county asylums in the period after 1845. The main facets of this regime were not

dissimilar to some of the recommended treatments today: a good diet, regular

exercise, recreational activities, religion and useful employment. This

treatment was outlined in the 1863 Garlands annual report by the medical

superintendent, Dr Clouston:

To treat the patients kindly, to maintain good order and discipline in

the house, to provide healthy and suitable employments for all who can employ

themselves, to endeavour to get those to work who do not do so, to provide

suitable entertainments for their leisure hours, to endeavour to get them all

roused into taking an interest in something, thus exercising and strengthening

the mental faculties they have left, and to keep up the bodily health and

strength in all of them.

He placed great emphasis on the employment of the

patients to act as a diversion from the thoughts and circumstances causing

their conditions: regular work for both

mind and body will do much to counteract the ill effects of the associations of

the persons, places, and circumstances that were connected with the original

outbreak of the malady.

Around

three quarters of the asylum population were regularly employed. Tasks in the

workshops, on the farm, and in the asylum itself were largely carried out by

the patients. The result was noted in the 1869 annual report as ‘pleasing and

amusing’ the patients to a great extent.

Patients, that were able, were allowed to walk in

the asylum grounds, with supervision from the asylum attendants, in order to

get regular exercise. This was said to have had a soothing effect on the

patient’s behaviour as they got the opportunity to clear their thoughts in the

fresh air. Similar to this were the recreational pursuits offered to the

patients to keep them usefully occupied whilst in the asylum. A large supply of

books and periodicals were available. Knitting, needlework, domestic chores,

work on the asylum farm, were all undertaken by the patients to encourage

productivity and recovery, as well as contributing to the upkeep of the asylum.

Regular events would be held to keep the patients occupied. Weekly dances and

balls would be held. Sports events, such as cricket, would occur, with teams

being brought in to compete with the patients. Choral groups, ventriloquists,

and lecturers would be invited in to the asylum to give performances.

Patients who were otherwise unruly could respond

well to these events. For instance, Catherine B, who was admitted in February

1885 suffering with mania and suicidal tendencies, seemed to forget all this

and react well to the asylum dances. As described in her case notes in April

1885:

Wanders about the ward moaning and groaning wretchedly. The only occasion

in which she appears to forget her troubles is at the weekly dance, when she

brightens up wonderfully. Laughs heartily and industriously goes round the

hall... Labouring hard often to teach others the steps and educate her fellow

patients who require it.

There are many instances of patients responding well

to the moral regime of the asylum. This was noted in the 1887 annual report: the disinclination many patients have shown

to leave the asylum, shows that the efforts made to treat the inmates justly

and kindly, and to render their life here pleasant and enjoyable, have been successful.

For

more background on Moral Treatment, see my previous post - http://garlandshospital.blogspot.co.uk/2015/09/the-moral-treatment-of-patients.html

Misconceptions

The main focus on my talk was to break down some of

the common misconceptions of the Asylum. These are the main three I have come

across. First: once patients were admitted, they were incarcerated for life. Overcrowding

of the asylum, and the pressure on accommodation in the institution was a

constant problem. As early as 1863, one year after opening, the Committee

of Visitors stated of Garlands: ‘they are

unable to provide sufficient accommodation therein for the number of lunatics

who are chargeable to the two counties.’ The asylum underwent several

extensions in its initial decades, taking the available capacity from 200 in

1862, to 660 patients in 1902. Taking this into account, the unnecessary

incarceration of patients simply was not feasible. Doctors were driven by

statistics, and were judged on their rates of recovery. So when a patient came

to the asylum, they did their utmost to affect a quick recovery, to maintain a

high rate of cure. As we saw in the Garlands recovery rates, they managed to do

this. Therefore, it was in the doctor’s interests to keep the patients for as

little time as possible in order to free up any available beds, and so that

they maintained their professional reputation among the relatively new field of

psychiatry. How well this quick-turnaround actually worked is doubtful, as many

patients were readmitted to the asylum at a later date, often in a worse

condition than when they were first treated.

The second biggest myth is that the patients were

subjected to frequent brutality. The common belief is that asylums kept

patients constantly in chains or strait jackets. However, as I have shown

previous, the regime of moral treatment completely disregarded this practice.

Patients were treated with kindness and given the opportunity to adhere to the

moral therapy offered. When patients rebelled against this kindness, the

doctors only sought to use methods of restraint as a last resort. Violent

patients would firstly be placed in a single room on their own and given the

opportunity to calm down: Sedatives would also be administered. If the violence

continued, and they posed a risk to themselves or others, methods of restraint

would be sought. All patients who were placed in mechanical restraints had to

be recorded in a specific register, and this would be inspected by the lunacy

commissioners on their annual visits.

For instance, in 1891, it was recorded that eleven

patients had been put in seclusion for a total of 257 hours across the whole

year, and that one man had been restrained for 8 hours using sheets, and one

woman using the strait jacket for 15 hours, across the whole year. Therefore,

although mechanical restraint was used, it was only done so as a last resort,

and was not the common mode of treatment.

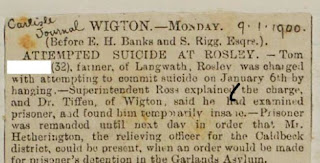

The last biggest myth is that patients, in

particular females, were admitted to the asylum against their will and without

suffering from mental illness. I often get people asking me if there are lots

of women put in there because they annoyed their husbands and such, but so far

I have found no evidence of this. I think that this practice may have occurred

in earlier decades and centuries among the wealthier classes who could afford

to pay doctors to take their wives into private asylums. But Garlands was a

public asylum that provided treatment for pauper patients, and was paid for by

local Poor Law Unions. The 1845 Lunacy Act stated that to be admitted to a

county asylum, the testimonies of two individuals that had witnessed the

person’s insanity had to be recorded on a document called a reception order.

These testimonies had to come from an examination from a doctor or medical

officer at the local workhouse, and from a relative/neighbour/fellow workhouse

inmate who had lived closely with the patient. The form then had to be signed

by a local magistrate warranting the person’s removal to an asylum. There are

instances of paper work being filled out incorrectly and patients being

discharged as a result. Therefore the method of entry to an asylum was much

more rigid than many people believe.

Next Steps

From the discussions began at the launch, it is

clear that more is required to really address the stigma surrounding mental

health. By using the past as a way of reflecting on how much (or how little)

treatments have changed, we hope to continue debating what is required in

future to treat mental illness.

The exhibition of the some of the Garlands archival

materials will be shown at several venues around the county. Full details and dates

will be confirmed shortly, and we hope as many of you as possible will be able

to view it.

For full information of the launch see

Any feedback of the event, and any comments you may

have for suggestions of where we could take the project, please don’t hesitate

to get in touch. Caradobbing@gmail.com